Phew! I did it! I climbed the roof of Africa, the highest crater of Kilimanjaro, Kibi mountain with the of height of 5895 m.a.s.l.

On the top of Kilimanjaro

Kili is a really marvellous and majestic

mountain, one of the highest free standing mountains. The first man who

climbed it was German geologist, Hans Meyer in 1889. For me it was the

first high mountain, that is why I will always remember it. You do not

need any creeper shoes, ice axis or ropes to climb it. People say that

the mountain is not difficult from the technical point of view, but I

know that it is hard to climb it if you are not in good shape,

especially during the hill-climbing attack. However, lot of people do

not reach the top mainly because of the height and problems with

pressure, not because of bad shape.

In the age of Internet

arranging an agency, the route and defining costs was no problem. For

$1000 each we were to climb the peak within 6 days taking the Machame

route– the most difficult one, which the locals call the Whisky Route,

as opposed to an easier route, Marangu, i.e. the Coca Cola route. The

other group of 8 doctors decided to take the Coca Cola route. I and my

brother have taken Machame route. Before we left Poland the Sobiepański

Trocha Graphic Studio had made a poster for the Foundation, which we

were going to unwind when we reached the peak.

The poster had to be

made of light but also very durable material since our journey through

Africa was to take almost a month. At the press conference I informed

journalists that the members of the Patient Safety Foundation had

planned to climb Kilimanjaro, I also told them about our campaigns to

get patients involved in hospital activities and the treatment process

by informing doctors, nurses and hospital administration employees about

their needs and plans of changes to be introduced. They wished us every

success on the route. Providing information on the trekking I wanted to

make people interested in issues related to patients safety, emphasize

what could be done together and how.

Jambo – Good morning!

We spent the night before the trek in Arusha,

small town near Kilimanjaro. We could not fall asleep for a long time,

so we observed the starry African sky. We packed only the necessary

things into our backpacks, I remembered to take the head flashlight

batteries, cap, gloves and trekking poles. I decided not to take any

books because I thought that my free time would be fully devoted to

establishing international contacts. Early in the morning the driver

came to take us and put our luggage in the land rover.

The first day

we were walking through the tropical forest. The way was quite easy,

the guide asked us to walk “pole, pole”, which means more slowly. I must

admit that I grew fond of the Swahili language from the very first day

because it was like a revision of the “Lion King” language. “Mzungu”

means a foreigner, “karibu” means please, the greetings “jambo” and

“mambo” have been in our dictionary for a long time. In the forest we

enjoyed observing monkeys but dampness and ubiquitous insects were quite

annoying. We reached the first camp after 5 hours. We put up our tents

between people from Germany and France. We were at the level of 3100

metres.

Snows of Kilimanjaro

It was damp in the tent. I woke up a few times

during the night. I got up in the morning because I felt pain in my

back. Our steward brought two small bowls with water and hot tea to our

tent. The sun was rising, the sky was so clear that it seemed almost

transparent. We could see the snow-capped Kilimanjaro for the first

time. Our clothes dried in the sun in a few minutes. African mice darted

from under our feet.

On the second day we reached the Shira camp at

the level of 3800 m.a.s.l. The route was more difficult, more rocky,

but the view was spectacular. For the first time I saw lobelias, cactus

trees, which were integrated into the lava fields. We caught the rhythm

of the trekk slowly: we woke up in the morning, had a wash and ate

breakfast. Every day we took our lunch on the route: hard-boiled egg and

a toast with butter. On the trek we could admire different landscapes

each day.

We could not expect we would be the only people on the

route, and groups of mountain hikers walked one after the other as in a

busy street. We could also see carriers who were jumping or running with

heavy objects on their heads. They were always cheerful, which

sometimes seemed unbelievable to “Mzungu” people. There were people of

various nationalities on the route. They greeted each other and talked

mostly about what to do to reach the peak.

Hakuna Matata

The expression means “no problem”. You need to

drink three up to four litres of liquid daily, follow the guide’s

instructions and climbing the peak will not be any problem. Today’s

morning I looked up at the breakfast wall and I thought that would be

the end of the mountain climbing. I saw a vertical wall, no paths for

me. Raphael, our guide, began to laugh when he heard about what I was

afraid of. It was only two hours of climbing on rocks. In his opinion it

was no problem and he advised me to leave my poles with the main

luggage. He said I would not need them that day. He was right, the route

turned out to be tolerable, however, at some points I thought my legs

should be a few cm longer to make walking more comfortable. That day we

walked to the Karanga Valley, i.e. the last place when water was

available. We filled all containers and bottles with water and set off

towards the Baraf camp. When we got there at 4 p.m. we were very tired.

We had a light meal the cook had prepared for us and the guide told us

to have 5 hours of sleep. It was easy to say. I remember that my brother

was reading the bible when I fell asleep. Just before midnight one of

the carriers woke us up, gave us some tea and encouraged us to get ready

for the hill-climbing attack. That night we were to reach Stella Point

at the level of 5745 m.a.s.l., and then the peak, the Uhru Peak. It was

to take us about six or seven hours, until dawn. We lit up our

flashlights and followed the guide. The rest of the group was to wait

for us in the camp. We were in good moods. I was glad because my

afternoon headache eased off. I felt cheerful and fresh.

After one hour of marching I saw some hikers walking down the hill with headache and nose bleed.

I

went through the night’s climbing attack in silence. The guide told us

to spare oneselves and talk only during short breaks when we were

drinking tea. I remember the guide’s boots very well since I was looking

at them to follow his tracks. I did not have to think too much, I was

just walking. When I was gasping for breath I stopped for a while and

then began to walk again. At some points I was weary of the monotonous

march. Then I turned back and saw Moshi shimmering with lights below.

For the last section from the vantage point, Stella Point, I was

crawling. My brother was running up for the last 700 metres to the peak.

When I touched the board on the peak my eyes were filled with tears. We

unwound the poster with fingers numb with cold. All people that were on

the mountain peak at that time came up to us and asked us what we were

doing and why we should care about patients safety. I was so tired that I

almost could not speak and it was only in the Barafu camp that I

answered all their questions. The Toya TV programme reporter asked how

many more peaks the Foundation members were going to climb in the

future. We have already been to Nepal, Pakistan, and Africa. We want our

members, volunteers and patients to talk about what we do. Just after

the expedition I was travelling by bus for 24 hours to get to Kampala in

Uganda. On 3rd November 2008 a meeting was held there, in which

organizations dealing with patients’ issues participated. The meeting

was attended by representatives of many African countries, such as

Tanzania, Kenya, Uganda, Nigeria, Zimbabwe, Ghana and the Republic of

South Africa. I managed to talk to them and find out what the

patient-focused care was like in their countries, share experience on

joint actions of European and African leaders in patients safety

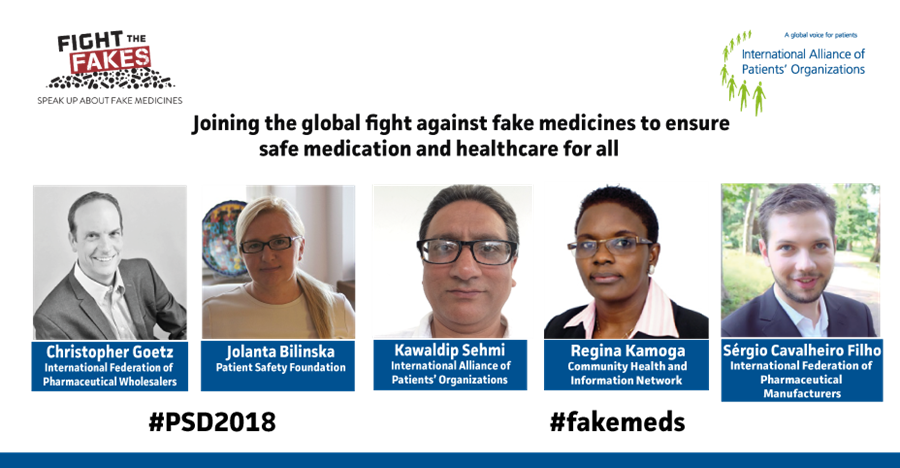

movement. It was thanks to Regina Namata Kamoga and Robina Kairitimba

that I could visit the Mulago hospital – the sickle cell anaemia

laboratory and see how the chain project works, which is a centre for

activity, education and promotion for children and young people in

Kampala, whose parents died of AIDS. Over 70 children in the centre

learn basic every-day life skills, how to use Internet and communicate

with others.

chain Kampala

The meeting in Kampala proved again that patients safety issues reach beyond geographic borders. We can all act together to make care over patients even more perfect.

Sickleceel association Uganda